Lost Species, Lost Seaweed, Dead Eels: 40 Years on the Taranaki Coast

Te Kahui O Taranaki assists Hapu in figuring out how to protect the coast when the ban ends.

photograph: tekorimako taranaki

Parihaka Kaumatua, who patrols the Taranaki coast, says it will take years to restore the devastated marine ecosystem.

A legal ban on shellfish gathering strengthens existing customary lahui and extends from New Plymouth to Opunake.

Another Rahui covers most of the coast from there to Hawera. This has been prompted by both the visitor cars and buses that have bared the reef over the past few years.

But Te Fiti O Rongomai Mason, the great-grandson of the Prophet of Parihaka, has seen a decline over the decades.

Mason, now in his 70s, spent much of his childhood with queers who lived on the coast where Kaimoana was abundant.

He left for Wellington in 1971 and returned in 1999.

“When I got home and got down to the shore, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing,” he said.

“Because the seaweed is gone, it’s completely gone.”

Coves that were overgrown with various seaweeds and algae were bared, depriving marine life of food and shelter.

He first saw the decline when he visited his home for tangihanga, and saw it accelerate as the use of urea fertilizers on farms increased from the 1980s.

“Once the urea came in and was placed in the farm, it ran out into the river. We also monitored dead eels. We saw dead eels at the mouths of rivers along the coastline.”

Mason was taught ticanga for gathering chi by his queers who lived here on the coast near Cape Egmont.

photograph: tekorimako taranaki

Mason now travels several times a week along the Palihaka coast between the Waiweranui and Waitaha rivers, checking out the reefs and pools, especially during low tide.

He had detailed knowledge of the species that lived there in his youth, and said many of them disappeared, including silver paua and various mussels.

“There are many types of limpets. When everyone sees one limpet, they think it’s the only one, but there are many different types of limpets. is gone.”

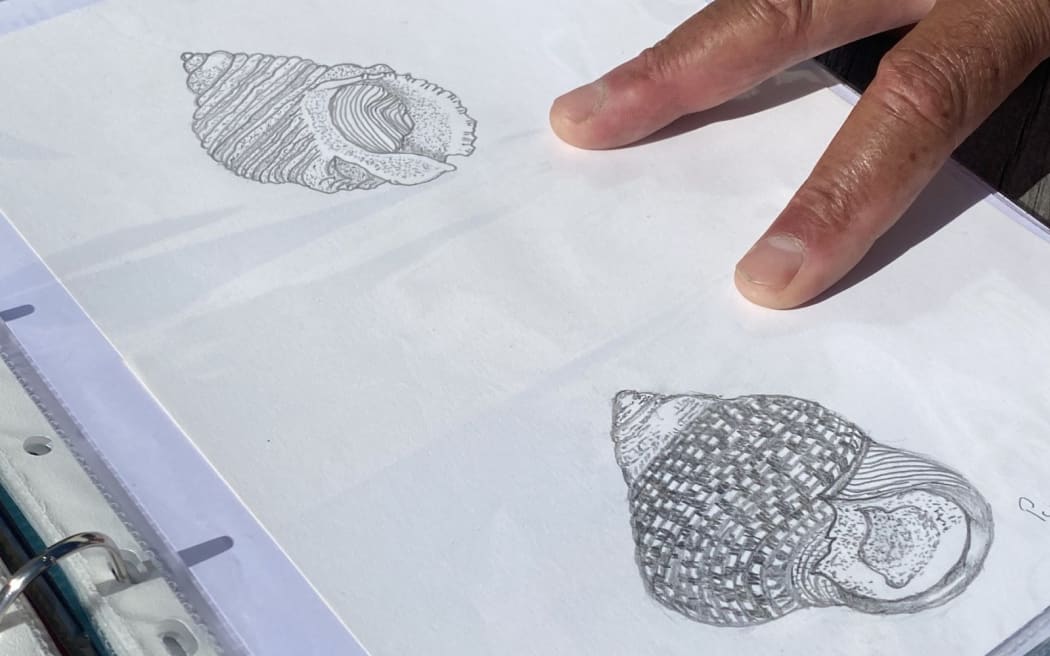

Mason submitted drawings and descriptions of shellfish and other coastal species, including those not currently present on shores, to petition the Marine Minister for a legal ban.

“When I was a kid, there were certain rocks and karekawa. [Cook’s turban shell] They used to breed under rocks, but they used to live in thousands under rocks, but now they are rarely seen.

He has seen signs of seaweed recovery in one small spot since Rahui began.

“Now I saw a part of our beach by the lighthouse. A certain seaweed put the paua and everything back. I see it covered.”

Mason said natural recovery would take years, but he hopes that scientists who volunteered to help during Rahui’s period may be able to hasten the recovery.

“We could have them take that growth, remove it, plant it, and regrow it. That’s the only way they’ll survive.

“It’s the seaweed that restores not only kina and paua, but everything from limpets and snails, to things that are usually found in tide pools, small shrimp, and so on.”

Mason submitted detailed drawings of the once common shellfish.

photograph: tekorimako taranaki

Te Kāhui o Taranaki is coordinating a legal ban application by hapū and is investing $500,000 to ensure more permanent protection when the ban is lifted.

Coastal assessments provide evidence of possible applications to set Mahinga Mataitai. Traditional fishing is permitted in the Mataitai Reserve under locally determined rules, and commercial fishing is generally prohibited.

Mason said Tikanga, which he learned from an old man in Palihaka, was complex, rigid, and seasonal, and was at odds with the assumption that people could go to the reef whenever they wanted.

A recent community meeting suggested that legal rules allowing only the largest paua to be taken are inconsistent with traditional practice. Smaller shells were found in local middens, suggesting that larger paua were left for breeding.

“Those paua were collected at certain times of the year. The smaller ones were collected in March, but only then were the smaller ones collected,” Mason says.

“We were shown which ones to take and which ones not to take, so you left a big one behind. You had a very small kete. It was so small that it didn’t exist. When that little kettle was full, it was.”

In some places it was possible to take the paua from the pool, but those under rocks were prohibited.

Mason says Rahui would help, taking the pressure off the coast, but the pollution had to be controlled.

“Our rivers are the problem. This is a big problem. Many small rivers and streams are polluted along here.”

“I’m still seeing dead eels. Just the other day, I saw four dead eels at the mouth of a river.”

Local Democracy Reporting is public interest journalism funded through NZ On Air.

https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/ldr/486697/lost-species-missing-seaweed-dead-eels-40-years-on-the-taranaki-coast Lost Species, Lost Seaweed, Dead Eels: 40 Years on the Taranaki Coast